The Art of Emulsification in Sauces and Dressings

Ever tried making mayonnaise from scratch and ended up with a broken, oily mess? You’re not alone. Emulsification sounds like something from a chemistry textbook, but it’s actually happening every time you whisk together oil and vinegar for a simple salad dressing.

but: understanding how emulsions work will change the way you approach sauces and dressings forever. And the best part? It’s not nearly as complicated as it sounds.

What Actually Happens When You Emulsify

Oil and water don’t mix. You’ve heard that a million times because it’s true. They’re like two people at a party who refuse to talk to each other. But emulsification is basically forcing them to get along by introducing a mediator-an emulsifier.

When you whisk oil into water (or vice versa), you’re breaking the oil into tiny droplets. These droplets want to merge back together. That’s why a basic vinaigrette separates if you leave it sitting on the counter. The oil droplets find each other and reunite, leaving you with that familiar layer of oil floating on top.

Emulsifiers prevent this reunion. They’re molecules with a split personality-one end loves water, the other loves fat. Egg yolks contain lecithin, probably the most famous emulsifier in cooking. Mustard has emulsifying properties too - so does honey. These ingredients wrap around oil droplets and keep them suspended in the water-based liquid.

The Two Types of Emulsions You Make in Your Kitchen

Not all emulsions are created equal. There are two main types, and knowing the difference helps you troubleshoot when things go wrong.

Oil-in-water emulsions are what you’re making most of the time. Mayonnaise, hollandaise, and most creamy salad dressings fall into this category. Tiny oil droplets are suspended in a water-based liquid. These tend to feel lighter and less greasy on your palate.

Water-in-oil emulsions work the opposite way. Butter is actually a water-in-oil emulsion-tiny water droplets trapped in fat. These feel richer and coat your mouth differently.

Why does this matter? Because the ratio of oil to water affects stability. Pack too much oil into an oil-in-water emulsion and it breaks. The emulsifier can only wrangle so many oil droplets before it gives up.

Temperature: The Variable Most People Ignore

You could have perfect technique and still fail because your ingredients are the wrong temperature.

Cold eggs don’t emulsify well. The lecithin in the yolk works best at room temperature. This is why so many mayonnaise recipes specifically tell you to use eggs that have been sitting out for 30 minutes. Cold oil is also problematic-it’s thicker and harder to break into those tiny droplets.

But here’s where it gets interesting. Butter-based sauces like hollandaise and béarnaise need careful temperature control for the opposite reason. Too hot and the eggs scramble. Too cold and the butter solidifies. You’re working in a narrow window, usually between 145°F and 160°F.

I once ruined an entire batch of hollandaise because I got distracted and let the water boil under my double boiler. Scrambled egg sauce - not appetizing.

The Slow Pour Method (And When to Skip It)

Every cooking class teaches the same technique: add oil in a thin, steady stream while whisking constantly. This works because it gives the emulsifier time to coat each new batch of oil droplets before more oil arrives.

But you don’t always need to be that careful.

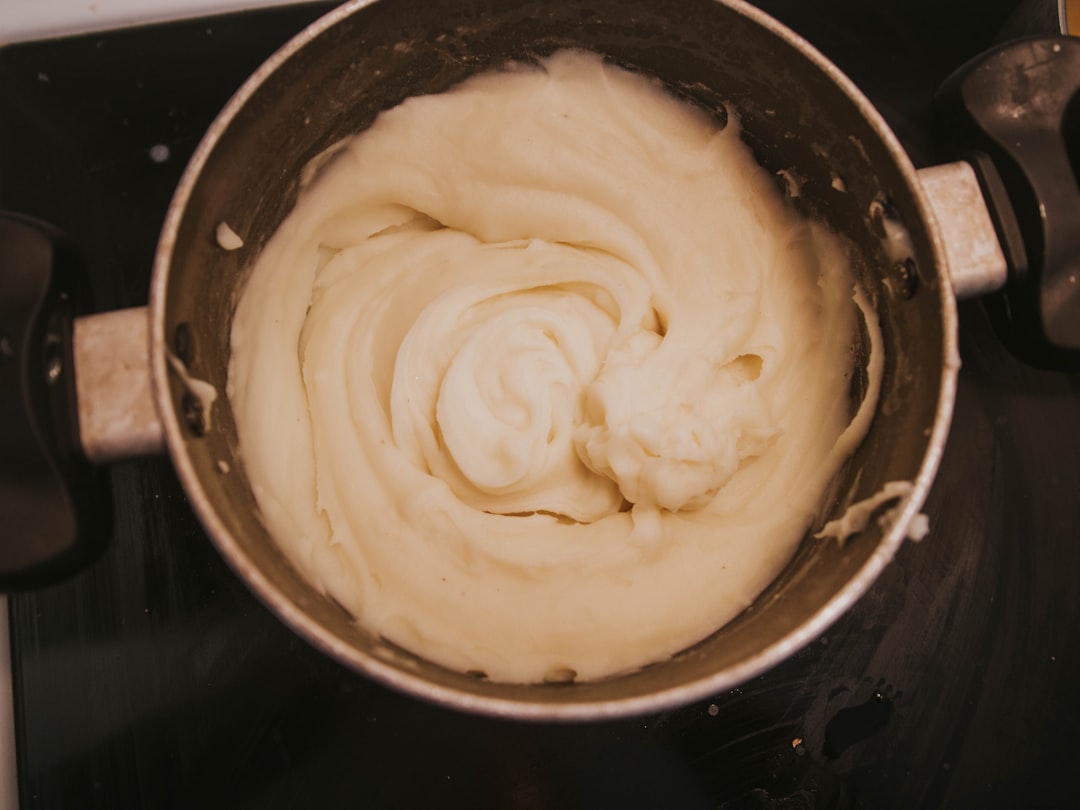

For mayonnaise, yes, start slow - really slow. The first few tablespoons of oil are critical. Once your emulsion has established itself-once it looks thick and creamy-you can add oil faster. The existing emulsion helps stabilize new additions.

For a simple vinaigrette with mustard as your emulsifier? Just dump everything in a jar and shake vigorously. Seriously. The mustard isn’t as powerful as egg yolk, so these dressings will separate eventually anyway. No point being precious about it.

Blenders and immersion blenders change the rules entirely. The mechanical force breaks oil into droplets so efficiently that you can often add ingredients all at once. Immersion blender mayonnaise takes about 30 seconds and almost never fails.

Fixing a Broken Emulsion

So your sauce separated - it happens. Don’t throw it out.

For mayonnaise or aioli: start fresh with a new egg yolk in a clean bowl. Slowly whisk your broken sauce into the new yolk, treating it like oil. The fresh emulsifier will wrangle those separated droplets back into submission.

For warm emulsions like hollandaise: if it’s just starting to look grainy or thin, immediately remove it from heat. Add a tablespoon of cold water and whisk vigorously. The cold water shocks the emulsion and can bring it back together. If that doesn’t work, try the egg yolk method mentioned above.

For vinaigrettes: just shake or whisk before serving. These are temporary emulsions by nature. Some cooks add a bit of mayonnaise or an extra teaspoon of mustard to help them stay together longer.

Building Better Dressings from Scratch

Once you understand emulsion principles, you can improvise confidently.

The classic ratio for vinaigrette is 3 parts oil to 1 part acid. But that’s just a starting point. Want something lighter - go 2:1. Making a dressing for bitter greens that need more richness? Try 4:1.

Your emulsifier choices affect flavor, not just stability:

- Dijon mustard adds sharpness and a slight heat

- Whole grain mustard gives texture and a mellower flavor

- Egg yolk creates richness and body

- Tahini adds nuttiness and protein

- Miso brings umami depth

- Honey contributes sweetness and mild emulsification

I keep making this tahini-miso dressing that’s absurdly stable. The combination of tahini (which contains natural emulsifiers) and miso creates something that stays mixed in the fridge for weeks. Add rice vinegar, a little maple syrup, some grated ginger, and water to thin it out. That’s it.

The Science of Thickness

Wonder why some mayonnaises are thick enough to stand a spoon in while others are barely thicker than cream? Several factors control thickness.

Oil ratio matters most. More oil means thicker results, up to a point. Standard mayonnaise contains about 70-80% oil by volume. Beyond that, it becomes unstable.

Emulsifier concentration helps too. An extra egg yolk makes for sturdier, thicker mayo. This is why aioli, which traditionally includes more yolks, tends to be denser.

Mechanical action affects things in surprising ways. Whisk mayonnaise by hand and it stays loose. Use a food processor and it gets stiffer. The processor creates smaller oil droplets packed more tightly together.

And acidity plays a role. Lemon juice doesn’t just add flavor-it tightens the protein structure of egg-based emulsions. This is why some recipes add acid at the end as a final thickener.

Practical Tips That Actually Work

After messing up more sauces than I’d like to admit, these are the habits that stuck:

Always have room-temperature eggs available. I keep a few on the counter specifically for sauce-making.

Use a bowl that’s narrower than you think you need. This keeps ingredients in contact with your whisk, making emulsification easier.

When making hollandaise, keep a small bowl of ice water nearby. At the first sign of curdling, dunk the bottom of your pan in the ice water and whisk like crazy.

Taste your base liquid before adding oil. The flavor concentrates as you build the emulsion. A dressing that seems perfectly seasoned at the start will taste underseasoned when you’re done.

Store emulsified sauces properly. Mayo and aioli last about a week refrigerated. Warm emulsions should be used immediately-hollandaise doesn’t reheat well.

Why This Matters Beyond Recipes

Understanding emulsification turns you from a recipe-follower into an actual cook. You start seeing the underlying pattern: an emulsifier, a fat, a water-based liquid, and mechanical force. That’s it.

Once you’ve got that framework, you can improvise. Swap out ingredients - fix mistakes on the fly. Create new combinations without needing a recipe to hold your hand.

And honestly? Watching oil transform into creamy mayonnaise never stops feeling a little like magic. Even when you understand exactly what’s happening chemically, there’s still something satisfying about making two opposing ingredients work together.

So grab some eggs, some oil, and a whisk. Your next sauce is waiting.